The Wobbly Table Problem

Note: I’ve written an essay about why I got interested in this problem

The Wobbly Table Problem: Given a continuous function , is it always possible to place a square table of fixed side length on the graph so that the the bottoms of each table leg are simultaneously in contact with the graph?

In other words, if you sit down at a table in a restaurant, and the table wobbles, can you always pick up the table and rearrange it so that it doesn’t wobble? The graph of the function represents the curvy floor on which the table is supposed to stand.

There are multiple ways to interpret this problem, so we’d better fix an interpretation before continuing. For example, do we want to insist that the table be level, in addition to being stable? What if the table is very short, so that the floor would poke through the tabletop unless we made the table taller? If the table isn’t level, the floor might poke through the table legs as well, do we want to allow that?

So let’s fix the following interpretation: First we don’t insist that the table be level. If our function were (for example) , then our table wouldn’t have a chance of resting level, and it can be made stable (non-wobbly) by placing the four legs at an incline along the -axis. So to make the problem interesting we shouldn’t require that the table be level.

Second, let’s actually make the table legs and table top permeable, and only pay attention to the bottoms of the table legs. Now we don’t need to consider whether the floor is so lumpy as to poke through other parts of the table, and we can focus our attention only the configuration on disembodied 4-tuples of points in the configuration of a square.

A proof that doesn’t work

There’s a seductive proof strategy which is actually very difficult to make work. Here’s the rough idea:

- Place the table on the surface so that a pair of diagonal legs both touch the surface. At first, the other pair of legs will generally not be touching the surface. Maybe one will and the other won’t, or maybe they’re both hovering over the surface, or maybe one is hovering and the other is piercing below the surface.

- Fix the two diagonal legs which are in contact with the table, and rotate the table while keeping those legs fixed so that the other pair of legs are equally above or equally below the table. So for example if they’re equally above the table, you could take two wedges of equal thickness and fit them under the off legs and then have the table be stable. Let’s assume they’re above the table — the proof strategy when they’re below is basically the same. Call this Configuration A.

- Perform the following maneuver: push the table straight down, so that the two legs in contact with the surface pierce through, and the two legs which are above the surface (by equal amounts) exactly touch the surface. Call this Configuration B.

- We’ve described one way to get from Configuration A to Configuration B: push the table down. Now we’ll describe a different way to get from A to B: Rotate the table clockwise around its center by 90 degrees, all the while making sure to (1) keep the pair of diagonal legs in contact with the surface, and (2) making sure to keep the other pair of diagonal legs an equal distance above or below the surface.

- Since we start with the off-pair of legs equally above, and end with them equally below, and all the while they’re an equal distance above/below, then at some intermediate point they must be exactly on the surface. Since the first pair of diagonal legs always remains on the surface, there must be some point at which all the legs are in contact with the surface. Hooray!

The problem is in step 4: it’s not clear that it’s possible to rotate the table around its center while keeping the opposite legs in contact with the surface. And if it were possible, it might be that there’s more than one configuration like that, so which one do you pick? And even then, it’s not clear that it’s possible to ensure that the two other legs are equally above/below the surface during this process.

Anyone who objects “yes but it should be possible as long as the surface isn’t too wobbly” should be prepared to explain what “too wobbly” means, and how to make the rotation argument precise using their hypothesis of “not too wobbly”.

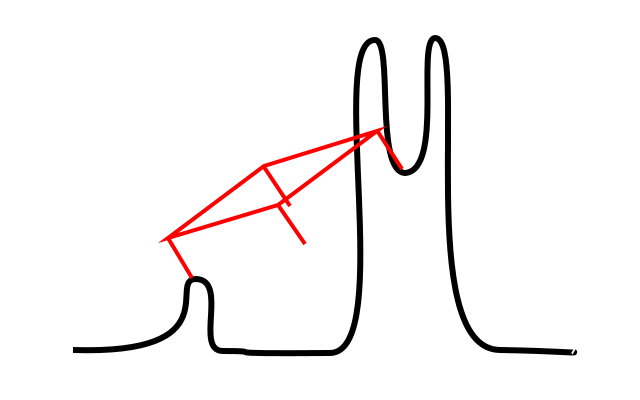

To drive the point home here’s an example of a surface where this strategy fails. One table leg is on the top of the short mountain at left, and the diagonally opposite leg is on the taller mountain-within-a-valley at right:

One successful attempt at making this proof strategy watertight is due to Bill Baritompa, Burkard Polster, and Marty Ross. Their proof has the advantage of also working for rectangular tables, and takes into account more realistic tables whose tops and legs are not permeable to the ground. The main downside (to my taste) is that restricts attention to surfaces which are not too steep — which locally do not rise by more than about 35 degrees. (Happily, most floors found in restaurants should be covered by their theorem.)

A theorem of Dyson

In 1951 Freeman Dyson proved the following theorem:

Let be a continuous function from the 2-sphere to the real numbers. Then there are two orthogonal diameters of the sphere whose endpoints and all take the same value of .

In other words, for any continuous function on the sphere, there are four points forming the vertices of a square on some great circle of the sphere, so that the function takes equal values on those vertices. It’s not immediately clear that it relates to tables, but it was noticed at least as early as 1970 by Roger Fenn that it implies the wobbly table problem. In fact George Livesay generalized this theorem to non-orthogonal diameters which Fenn notes resolves the wobbly table problem for rectangular tables as well as squares.

How does Dyson’s theorem resolve the wobbly table problem? Well, given the graph of a function representing the ground, take a function , where is defined on the standard 2-sphere embedded in 3-space. Now apply Dyson’s theorem to this function , and we find a square in 3-space whose vertices all have the same value of , or in other words all lie the same distance above or below the ground. Simply slide them up or down without moving the center side to side, and we’ve found a stable place for our table.

How, then, do we prove Dyson’s theorem? Dyson’s original proof is fairly short, just a few pages, but I found it unsatisfying because it makes use of unusual objects called -sets: sets which separate the origin in Euclidean space from infinity along any ray. The feeling I get is that he would have liked to use a more standard tool but was unable to get it to work. (Of course my feeling is only an opinion, not rooted in any specific knowledge about Dyson’s choices.)

To me, the flavor of Dyson’s theorem is very reminiscent of the famous Borsuk–Ulam theorem (the classic illustration of this theorem is that, at any given moment, there are a pair of antipodal points on the Earth’s surface with the same temperature and pressure). I sought — and found — a proof along the lines of the standard proofs of the Borsuk–Ulam theorem.

In part 2, I’ll explain my proof of Dyson’s theorem.